Facing Depression: Photographs from Dorothea Lange

Documenting the Great Depression’s Historical Realities

By Keith Bates

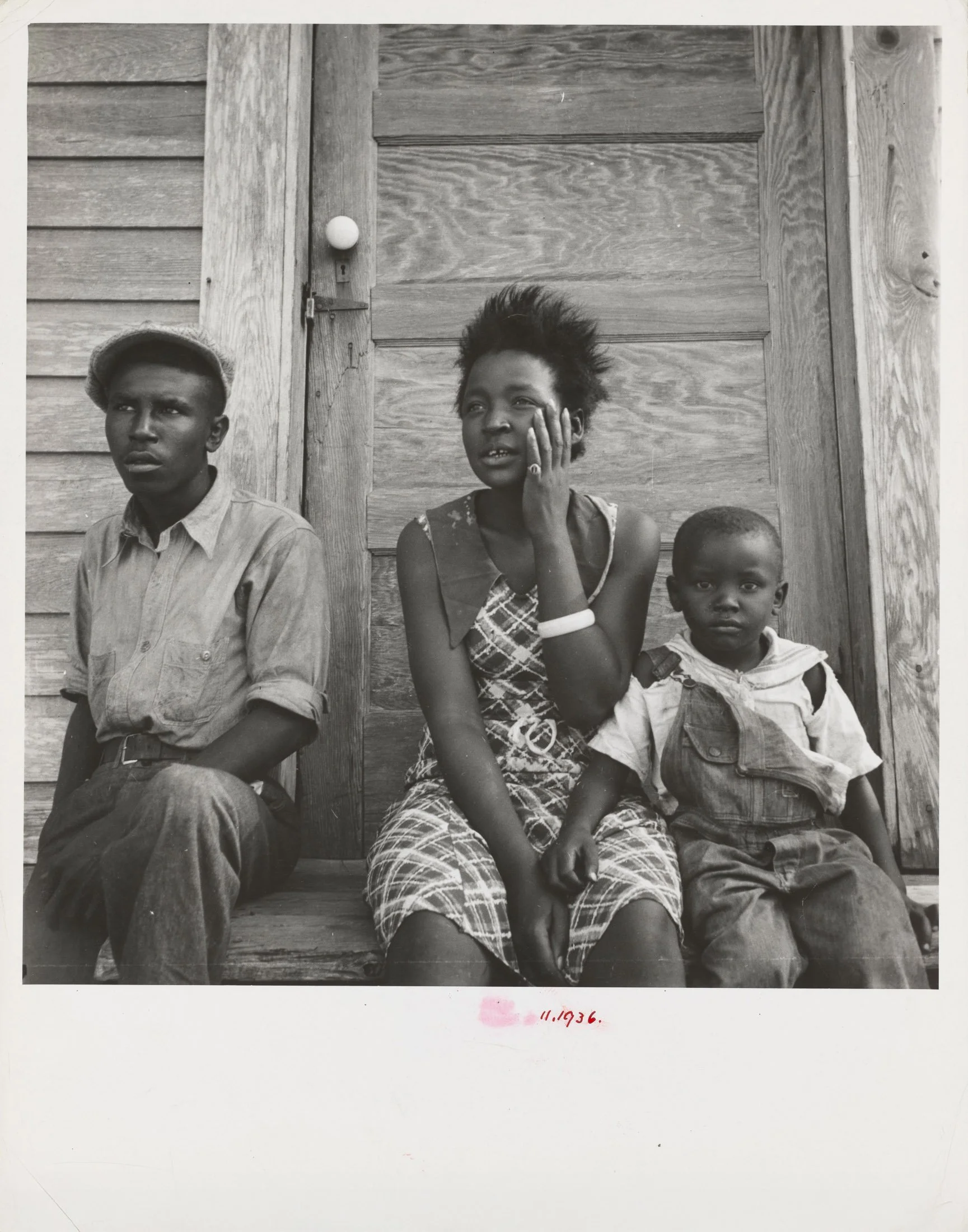

By the time Dorothea Lange began photographing migrant workers for New Deal agencies, the United States had been struggling under the effects of the Great Depression for the better part of a decade. During the five years she traveled around California, the Southwest, and the South, Lange captured images that documented the immense suffering caused by long-term unemployment and displacement. Although her work emphasized the struggles of Americans who had been forced into a hardscrabble existence, it is also evident from Lange’s photographs that these were people who refused to surrender to despair. In portraying the complexities and tensions of her subjects’ lives, Lange humanized the Great Depression for her contemporaries and thus prompted Americans to consider what could be done for those in need. Nearly a century later, Lange’s work serves as a testament to the difficulties that defined the lives of millions of Americans even as the nation embraced a new commitment to communal action to help them overcome their circumstances.

A popular but inexact interpretation of the era that Lange documented holds that the Great Depression began with the 1929 stock market crash and then proceeded to wreak havoc on the entire American population. To be sure, the events of “Black Tuesday” (October 29, 1929) did not cause the Great Depression, but they did contribute to the oncoming crisis by shaking public confidence in the economy and reducing the value of publicly traded companies.[1] It was after these initial problems were exacerbated by factors such as bank failures, reduced demand for agricultural and industrial products, and rising unemployment that a devastating economic depression emerged. By the time Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated as president on March 4, 1933, the gross national product was at half of its 1929 level, bank failures had cost depositors $7 billion, and millions of Americans had lost their homes to foreclosure. Unemployment, which proved to be the most effective measure of the citizenry’s misery, reached 25 percent of the workforce in 1933 and averaged just over 17 percent throughout the 1930s.[2]

While these challenges touched all Americans, long-standing inequities in American life meant that the Great Depression disproportionately affected groups such as African Americans, Mexican Americans, immigrants, and the rural poor.[3] Surveys conducted in the 1930s demonstrate how hard life became for these vulnerable populations. In 1933, for example, social workers in Atlanta estimated the jobless rate in some Black neighborhoods to be nearly 75 percent at a time when the city’s overall unemployment rate was closer to 30 percent.[4] The data that Lorena Hickok, chief investigator for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, collected when she visited communities across the country in 1933 and 1934 confirm the unevenness of the Great Depression’s effects. Much of what Hickok discovered could only be described as deprivation. In Eastern Kentucky, for example, she found that 62 percent of people living in ten mining counties would struggle to survive without federal relief.[5] During her travels, however, Hickok also became aware of the inequities that still existed in the United States. While their fellow citizens struggled to survive, Hickok once explained, millions of Americans found that the Great Depression had only made life a little harder.[6]

The ten million agricultural workers that lived in the United States were not among the privileged. In fact, their circumstances were much worse than those of most other Americans because their problems predated the stock market crash of 1929. After years of boom during and right after World War I, American foodstuffs declined in the mid-1920s after the European nations that had been buying American crops recovered to the point that they could feed themselves. Matters went from bad to worse during the 1930s as drought and Dust Bowl storms destroyed crops and as prices on all farm commodities fell at alarming rates. Even cotton, which had been consistently profitable during the first decades of the twentieth century, lost two-thirds of its value.[7] Failed mortgages on farms and the displacement of laborers seeking reliable jobs became common experiences for American agricultural workers.

Franklin Roosevelt reached out to farmers and others within vulnerable communities during his 1932 presidential campaign because he knew that desperate Americans were looking for solutions that the incumbent, Herbert Hoover, either could not or would not provide. While historians subsequently demonstrated that Hoover was more active than previous presidents had been in offsetting the nation’s economic difficulties, the majority of Americans were more inclined to blame rather than trust Hoover in 1932.[8] This is not surprising, especially because Hoover’s ideological rejection of an activistic federal government drove him to reject the type of major works programs that Roosevelt used to inspire hope among voters during the campaign.

From the beginning of his presidency, Roosevelt worked to keep his promise to establish “a new deal for the American people” by creating a government that would take on the nation’s problems.[9] Roosevelt’s administration largely accomplished this through its “alphabet agencies,” federal agencies typically known by their acronyms rather than by their official names. Notable agencies included the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), which employed young Americans to complete public works projects; the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority), which brought electricity to rural communities; and the AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Administration), which established policies intended to raise farm prices. Along with laws such as the Social Security Act of 1935, which provided old-age pensions and unemployment insurance, New Deal agencies extended basic social benefits to millions who had previously been excluded from key aspects of the American dream.[10]

By the end of Roosevelt’s first term, the nation had experienced more economic growth than it had during any previous four-year peacetime period.[11] But even with notable improvements brought by the New Deal, the nation was unable to overcome the Great Depression in the 1930s. Consequently, even though farmers, migrants, and the rural poor received increased attention and assistance from the federal government, their lives continued to be defined by struggle. We see their hardships in the nearly 65,000 images captured by Dorothea Lange and the other photographers who worked for the Resettlement Administration (RA) and its successor, the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Throughout the 1930s, RA and FSA photographs were printed in popular publications to “introduce America to Americans” and foster support for rural aid programs.[12] In the present day, these same photographs attest to the challenges that persisted even as individuals and the broader nation struggled to put an end to the Great Depression.

[1] David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford University Press, 1999), 38.

[2] Richard J. Jensen, “The Causes and Cures of Unemployment in the Great Depression,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 19, no. 4 (Spring 1989): 557; and Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 162-66.

[3] Roger Biles, The South and the New Deal (University of Kentucky Press, 1994), 9, 19; and Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 164.

[4] Biles, The South and the New Deal, 19.

[5] Thomas H. Coode and John F. Bauman, “‘Dear Mr. Hopkins’: A New Dealer Reports from Eastern Kentucky,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 78, no. 1 (Winter 1980): 57-63; and Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 170.

[6] Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 168.

[7] Eric Rauchway, Winter War: Hoover, Roosevelt, and the First Clash Over the New Deal (Basic Books, 2018), 80.

[8] Robert H. Zieger, “Herbert Hoover: A Reinterpretation,” The American Historical Review 81, no. 4 (October 1976): 800-10; and Biles, The South and the New Deal, 32.

[9] William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (Harper Torchbooks, 1963), 326-31.

[10] Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 378.

[11] Christina D. Romer, “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (December 1992): 757-84; and Rauchway, Winter War, 236.

[12] Linda Gordon, “Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist,” The Journal of American History 93, no. 3 (December 2006): 698-727; and “Farm Security Administration (FSA),” Museum of Modern Art, accessed July 21, 2025, at https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/farm-security-administration-fsa.

Exhibitions Date: August 13, 2025 - November 29, 2025

Curated by Aaron Hardin

Photographs from the New York Public Library